To the extent that historical press releases reference BMW Manufacturing Co., LLC as the manufacturer of certain X model vehicles, the referenced vehicles are manufactured in South Carolina with a combination of U.S. origin and imported parts and components.

PressClub USA · Article.

BMW NA 50th Anniversary | 50 Stories for 50 Years Chapter 8: “From Hoffman to BMW of North America: A Brand and its Dealer in Transition”

Mon Feb 24 18:46:00 CET 2025 Press Release

When BMW of North America took over from Max Hoffman on March 15, 1975, it inherited the dealer and distribution network that Hoffman had been building since 1962. Hoffman’s dealer directory of April 1967 listed 129 BMW dealerships and six independent distributors in charge of specific geographical territories. Though the network covered the entire US, dealerships were concentrated in the Northeast and on the West Coast: New York had 23 BMW dealerships, California 24. Vast areas of the country were entirely unrepresented; Texas, for example, had no

Press Contact.

Thomas Plucinsky

BMW Group

Tel: +1-201-307-3701

send an e-mail

Author.

Thomas Plucinsky

BMW Group

Downloads.

Related Links.

When BMW of North America took over from Max Hoffman on March 15, 1975, it inherited the dealer and distribution network that Hoffman had been building since 1962. Hoffman’s dealer directory of April 1967 listed 129 BMW dealerships and six independent distributors in charge of specific geographical territories. Though the network covered the entire US, dealerships were concentrated in the Northeast and on the West Coast: New York had 23 BMW dealerships, California 24. Vast areas of the country were entirely unrepresented; Texas, for example, had no dealerships at all.

After the 1600-2 and then the 2002 became unexpected hits in the US, Hoffman nearly doubled the number of BMW dealerships over the next eight years. More didn’t necessarily mean better, however, especially as Hoffman awarded dealerships in a less-than-scientific manner. In Burlington, Vermont, he reportedly offered a BMW franchise to a man who’d replaced the dead battery in his car late one Friday evening. In Tacoma, Washington, Hoffman charged Werner Scharmach just $1,500 for the signage and other equipment needed to become a BMW dealer. In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, he required Harold Zimdars to order just two BMWs to become a dealer.

“In the Northeast, we had a lot of small dealers, some with really inadequate facilities and almost all selling other brands,” said Tom McGurn, BMW of North America’s first public relations manager. “The West was better, but the Southeast had been almost forgotten. But there were some large-volume dealers, too, like Peter Pan in San Mateo CA and Knauz in Lake Forest, Illinois, near Chicago.”

Bill Knauz became a BMW dealer in 1971, after writing Hoffman a letter and then introducing himself to Hoffman’s sales manager (and brother-in-law) Michel Melamed at the New York Auto Show. Knauz’s dealership—established by his father Karl in 1934—already sold Mercedes, Citroen, and NSU, and he was looking for another line of small, low-priced cars. “I was ready to fight to get this franchise, and when I walked in Melamed said, ‘Well, Mr. Knauz, how many cars do you want in your first load?’ I had no financial arrangements, but he told me not to worry about that. ‘We know Lake Forest. I’ll send you sixteen cars.’ That was my negotiation for a BMW franchise.”

By the time BMW of North America took over US distribution from Hoffman in March 1975, Knauz’s dealership was one of around 250 in the country. A handful declined to carry on under the new regime—for some, it required a significant investment to meet BMW’s standards for corporate branding and presentation—but most agreed, and more dealerships joined the roster. When BMW NA published a new directory in September 1976, BMW automobiles were sold in 295 dealerships, some serving previously unrepresented areas of the Midwest and Southeast.

Adding more dealers was one thing. Improving relations with dealers was another. Hoffman had paid a significantly lower margin (14.2 percent) to BMW dealers than they could earn by selling Fiat or Volkswagen (16 and 20 percent, respectively), and he was inconsistent when it came to honoring warranty claims and stocking spare parts. “If Max didn’t pay warranty, I had to make it work out,” said Lee Maas, who began selling BMWs at his Classic Cars dealership in Dallas, Texas in 1970. “If he was short on parts, I made sure we had the parts to fix most anything on the car.”

Knauz echoed Maas’ complaints about Hoffman’s business practices—“He didn’t pay you properly on parts, service, warranty work, etc. He wasn’t too interested in what happened after he sold you the cars”—but said he had a good relationship with Hoffman himself. “After my father died, I became a pseudo-son to Max. He’d call me almost every Friday, speaking only German. ‘Why don’t you buy some more Bavarias?’ I’d say, ‘Max, I just bought two loads of Bavarias! I don’t need more.’”

As odd and informal as that relationship may have been, Knauz said it was preferable to what followed in the immediate aftermath of Hoffman’s dismissal. “I was not happy at all with BMW NA,” Knauz said. “The people they put in charge… They wanted to do business in a businesslike manner, while Max did business on a handshake. You couldn’t trust the handshake, but…”.

McGurn remembers it slightly differently. “Knauz embraced the businesslike approach, but his one caution was to move strategically rather than too quickly to get on a par with Mercedes, Volvo, Audi and other brands.”

Indeed, the new organization was nothing if not businesslike, to the benefit of the vast majority of its dealers and customers. Under the leadership of its first CEO, John Cook, BMW NA improved dealer margins and sped up the processing of warranty claims. The company also began holding dealer meetings, which Hoffman had refused to do.

“Hoffman did not believe in dealer meetings,” said Bob Lutz, BMW AG board member for sales from 1972 to 1974. “I said, ‘Maxie, we’ve got to have a dealer meeting, generate some enthusiasm, outline our marketing plan.’ He said, ‘Bob, you never want to get all the dealers in one room. That’s one of the rules. Because then they start comparing notes, and they figure out that I do things for some of them that I don’t do for others.’”

By contrast, BMW of North America began bringing its dealers together in late spring 1975. “We wanted to introduce the management team and present our plans to increase brand awareness and sales volume, and to support dealers and customers,” McGurn said. “Communication with the dealer organization was critical. Dealer councils were common in the industry, and we appointed the first dealers to our Dealer Forum that met twice a year and discussed their issues. Once organized, the dealers elected their own representatives. Some of the dealers were visionary, asking for a competitor to Mercedes’ S-class or for more technical support, as well as support from the company in the form of parts and service, sales and promotion.”

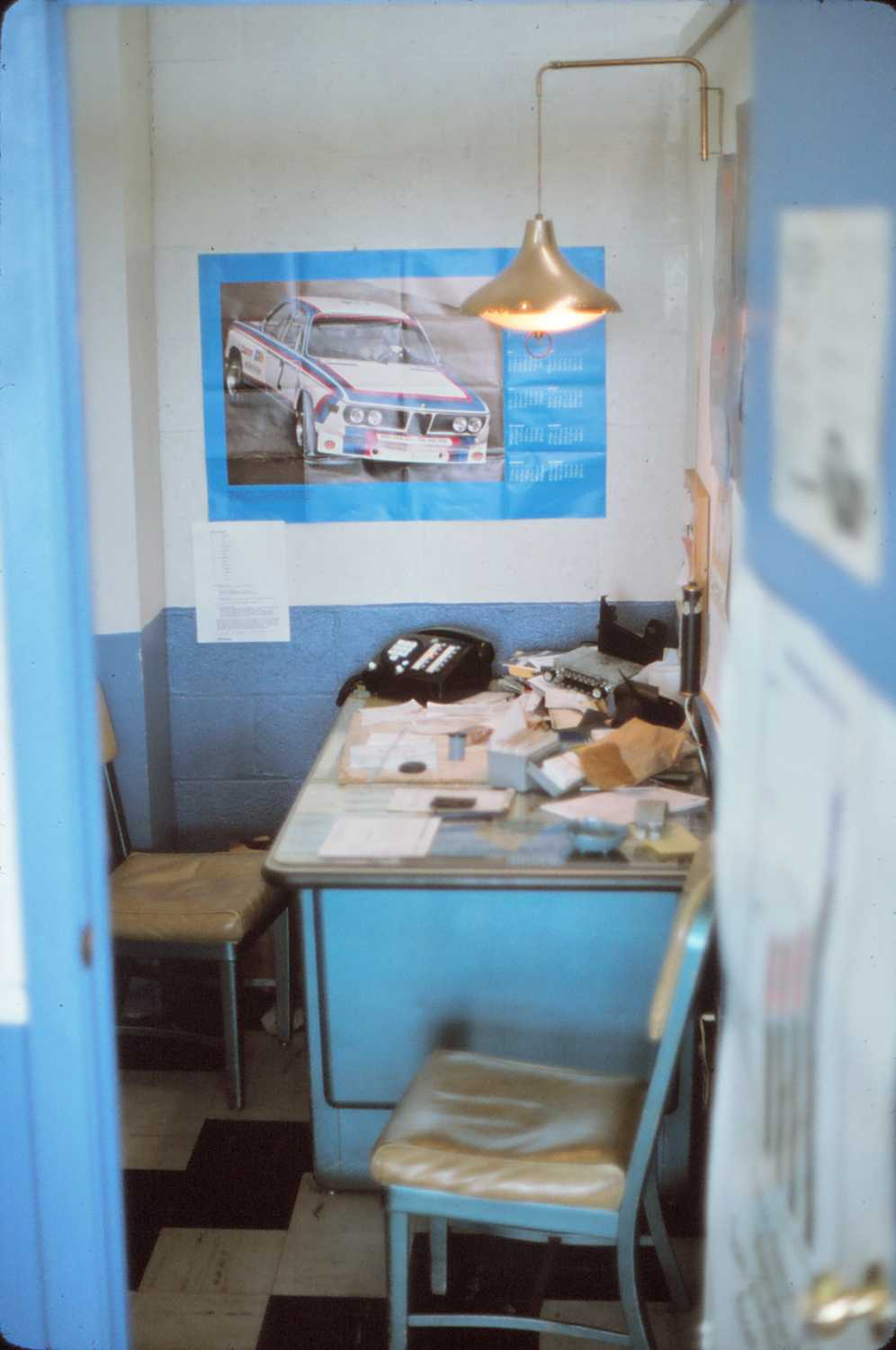

BMW of North America began advertising more heavily than Hoffman right from the start…and more effectively, too. A new tagline, “The Ultimate Driving Machine,” captivated enthusiasts, and so did BMW Motorsport’s successful campaign with the 3.0 CSL in IMSA racing.

In his first interviews with the US media, Cook told journalists that BMW of North America hoped to sell 18,000 cars in 1975. Instead, it sold 19,419, followed by 26,040 in 1976, and 28,776 in 1977. Sales would grow steadily for the next decade, a welcome development that nonetheless created challenges for the young organization and its dealers.

“The company grew perhaps too fast in those early days. BMW was the ‘in’ product to have, and the infrastructure couldn’t keep up with sales,” said Larry Demski, who joined BMW of North America as an engineering workshop technician in 1977.

Adding to that challenge, the first cars to arrive following the establishment of BMW of North America were far more sophisticated than their predecessors, incorporating more electronics than ever before.

“The technology on the cars was changing—we were among the first to have ABS, and airbags—and when the technology failed, we didn’t always have the infrastructure to repair it,” Demski said. “People would complain if the car couldn’t get fixed, or they couldn’t get parts. ‘It was billed as the Ultimate Driving Machine, but it doesn’t drive!’ The dealers would try, but they didn’t have the right diagnostic tools, or the right training.”

In the meantime, BMW of North America had expanded its sales network to some 400 dealerships by the end of the 1980s, which McGurn said was “way too many” for the number of cars being sold in the US. Compared to dealerships that sold other marques, BMW dealerships sold far fewer cars on average, limiting profits as well as each dealer’s ability to invest in and improve their business. This problem became especially acute when sales volume began slipping in the face of exchange-rate challenges and new competition from Japan: From 96,759 cars in 1986, annual sales fell to just 53,343 cars in 1991.

That period saw BMW NA and its dealers come under pressure from the introduction of new Japanese luxury brands, of which Lexus was the most successful. In lieu of a storied brand history, Lexus staked its reputation on a customer-focused dealer experience. Selecting the best and the most dedicated Toyota dealers to create separate showrooms and workshops for its new luxury brand, Lexus was able to build a right-sized dealer network while setting a new standard for customer care. Lexus’s commitment to customer service inspired a more customer-focused experience within BMW NA and its dealer organization; interestingly, since the new Japanese brand had launched first in the US, BMW’s new focus on the customer experience began in the US, too, before migrating to Europe.

BMW NA needed to reduce the number of dealerships, but US franchise laws restricted its ability to do so at will. Arriving at the right number would require a different strategy. “We decided we had too many dealers, and given the threat from Lexus, we needed to make the business case that consistent branding was essential, with respect to the appearance of dealer facilities, our national and local dealer advertising, customer experience standards, etc., which were needed for growth and profitability,” McGurn said. “We also emphasized the importance of exclusivity. In the beginning, BMW was often sold and serviced alongside another brand. The dealer in Manhattan, for example, had Volvo and maybe even Fiat in the same showroom with BMW. As volumes increased, BMW encouraged its dealers to create separate and exclusive facilities and staff for BMW, and we found that those that did were more focused on the BMW experience with respect to branding, sales, and aftersales.”

Some of the independent businesspeople who sold BMWs resisted those moves, and some stopped selling the brand altogether. Other dealers recognized the advantages and embraced the changes readily. “Some realized that if we all look alike, it builds the brand awareness, and then I can do things in my own dealership that will bring the customer to me rather than the other guy in the neighboring community,” McGurn said.

Creating a consistent BMW look in the showrooms was essential, and so was improving the technical training of dealership service personnel. By 1987, BMW was on the cusp of introducing the E32 7 Series, followed shortly thereafter by the E34 5 Series—by far the most advanced vehicles on the market at the time. The service and training methods that had served the brand up to that point wouldn’t be adequate to support the newest BMW vehicles.

“The technological leap forward with the E32, E34, E31 was a bit of a struggle for whole aftersales organization to catch up with,” said Tom Plucinsky, then a technical trainer for BMW Canada. “As an example, I remember going over to Munich for the 8 Series train-the-trainer seminar, and we spent 95 percent of our time going through the mechanical systems of the car, including dismantling and reassembling the M70 V12 engine. By contrast, very little time—maybe five percent—was dedicated to diagnosing the very sophisticated electronic systems in the car. Back in the US and Canada, we determined that our technicians would have much more difficulty understanding and diagnosing the advanced electronics than they would figuring out how to adjust the rear quarter windows. This needed to be the focus of our training”

In the wake of that epiphany, BMW NA developed a robust technical training program that focused on electronic side, starting with E32. This paid huge dividends in training North American technicians for a new generation of vehicles. “Gone were the days of diagnosing cars with a trouble light,” Plucinsky said. “As of the E32, BMW was in the age of computer-controlled systems throughout the vehicle, and our dealerships and technicians needed to be equipped and trained to be able to service these wonderful new models.”

In return for the commitment of its dealers, BMW of North America offered additional support from the corporate side. The establishment of BMW Financial Services in 1992 gave dealers access to the credit they needed to upgrade their facilities where both sales and aftersales were concerned.

From the marketing side, BMW NA worked with the dealers to form dealer advertising groups. The groups created BMW-branded ads that could be placed regionally and in major markets with each dealer listed at the bottom. “That way they could pool their money, get better efficiencies, and achieve a common, brand-supporting look,” McGurn said. “We produced some of those ads nationally, and others were produced by regional agencies that dealers picked, and which created ads under brand guidelines.”

At the same time that BMW NA was emphasizing its brand identity through marketing, the company began encouraging (and enforcing) the use of best practices for customer service, from the condition of waiting rooms to the technical proficiency of dealer service departments.

“It was a concerted effort to make sure the dealer was representing the brand the way the customer viewed the brand, and the way the brand should be represented,” said Demski. “Some dealers were not passionate at all about the product, and they just looked at it as a dollar-and-cents thing. You had to have tough conversations to make sure those dealers understood that their practices—failing to keep the batteries charged, for example, which would lead to premature battery failure after the car was sold—could lead to customer dissatisfaction. We created a Retail Operations Manager to focus on sales processes, service, and parts, and to explain what proper processes should be. We also offered a lot of training for service technicians and reached out to technical schools to attract people who were educated on modern technology.”

In addition, BMW initiated—and the Dealer Forum endorsed—the concept of a “cost per vehicle” program that pools a portion of the wholesale price of each car sold to help dealers pay for the training and tools needed to service ever-more-sophisticated automobiles. “That was quite revolutionary,” Demski said. “It ensured that no matter what size the store was, it could get training and tools. No other OEM has that, and we’re the only country that has it among BMW organizations.”

BMW of North America’s efforts to improve brand management and customer service at the dealer level achieved impressive results. After hitting a low point in 1991, sales have improved steadily ever since, the sole exception occurring during the financial crisis year of 2009; even then, BMW NA weathered the storm better than most.

The company was also successful in “right-sizing” its dealer network following its over-enthusiastic expansion of the ’70s and ’80s. Today, the BMW Group is represented by 349 automobile dealers, plus 145 motorcycle retailers, 104 MINI, and 38 Rolls-Royce dealers, all of which meet or exceed BMW of North America’s standards for representation and customer service.

—end—